Welcome to Beyond This Moment! If you’re reading this, you almost surely know me personally so I’ll spare the extended introduction (if not, here’s a LinkedIn for your troubles). I believe writing is its own form of learning, of challenging yourself to put down thoughts and arguments in ways that can withstand scrutiny and time. It’s been an important part of my personal journey - being challenged to do NaNoWriMo in 7th grade pricked the itch, and I wrote constantly throughout high school and college as part of the school newspapers.

My college body of work is a good model for what this blog will be: a combination of pure opinion and data analysis focused on sports, business, education … and mostly whatever strikes me that week. Over time, it will find its voice and themes. Living in Silicon Valley, there’ll be a myopic focus on my immediate surroundings, starting with this week’s post.

The unsubscribe button is a click away - find it, or keep on!

---------------

When I moved out to San Francisco in 2018, I knew close to nothing about venture capital. “VC”, as most folks refer to it, is largely (but not exclusively) an American practice and, within that, a West Coast practice. A 2017 survey found that of the top 100 firms in the world, 70 hailed from North America (they raised 73% of the total money, so it’s not a clustering at the bottom either). Fifteen of the top 20 are American, and ten of those are in Silicon Valley. In the South Bay, where I now live, five of the top 7 firms work in a 20-mile radius – most on the same street (the (in?)famous Sand Hill Road).

It’s hard to argue what’s the chicken and what’s the egg, but Big Tech has blossomed in the same part of the country due to a close partnership with the VC industry. Tech companies are perfect matches for the venture model because of their ability to scale at minimal variable cost, and over recent years anywhere from 25 to 40% of all US venture money flows into companies started in the Bay Area. If you’re not in VC, its investment dollars still probably pay your rent.

VC is a form of early-stage investing - at a high level, it’s finding companies early in their life cycle, buying 15-20% in a cash injection that gets it off the ground, and (ideally) re-investing and nurturing them as they grow. The risk is much higher because you’re investing in unproven business models (and, often, twenty-somethings with minimal resumes). But, at the end of the day, it’s still investing - more like private equity or hedge fund work than building a company.

Big picture: out here venture capitalists matter - a lot. The successful ones are ‘household’ names in the tech/finance space (Chamath, Andreesen, Paul Graham, Sam Altman) who publicly present as the ancestors to Plato’s philosopher kings. They spend a lot of time thinking out loud - on how to be successful, how to set your schedule, how to be rich, etc.

Inspired by a question I got recently - from a college student curious about how to break into venture, I began wondering about how exactly one becomes a venture capitalist. The path for other forms of finance (private equity, hedge fund) is pretty direct:

Go to a top 20 US school (the higher the ranking, the better)

Go to an investment bank right out of school

Spend 1-2 years getting your butt kicked, learning a lot, and make the transition

Wall Street is generally shamelessly elitist. Everyone is Hester Prynne, wearing your undergrad university as the scarlet letter - it comes up often, for better or worse. Venture doesn’t have the same reputation. It projects a founder-friendly persona that it will take talent from anywhere, and disdains college background (some local titans even encourage you to drop out).

A sample bio from a VC website

I got curious and checked it out. Lacking imagination (or advanced scraping skills), I had a simple methodology. Find the top venture capitalist firms and use their websites to find their investors. Then, LinkedIn - where you can get reliable data on where folks did their undergrad, grad school, and what they were doing before they ended up in venture. I looked at 10 firms - Sequoia, Accel, a16z, Lightspeed, Insight, General Catalyst, Index Ventures, Greycroft, Google Ventures, and Bessemer - finding around 450 US-based investors. It’s a big enough cross-sample to be pretty representative. So while I won’t pass this on as peer-reviewed science, there’s enough here to draw some lessons.

Lesson #1: School still matters, a lot

I don’t have hard reference data on what % of investment bankers go to top schools, but from memory about half of the folks I met in banking went to an Ivy League (or similar) school. The few common exceptions were traditional business schools - University of Michigan, NYU, Ivey, Queens, etc. My group had analysts from George Washington, Wellesley, and Penn State but those schools weren’t well represented.

Venture is even more clustered.

Of the investors I looked at, 40% had their degrees from the Ivy League. Another 11% went up the road to Stanford. If we broaden the group to include other top US schools (using the top 20 of the US News rankings), it’s 2 in every 3 people. Firms don’t vary much in their elite focus.

Of the top schools, there’s a pretty significant gap between the main trifecta and everyone else. Harvard and Penn each have about 50 grads here, and Stanford has 45. The next schools - Princeton and MIT - have 16. As we see later, those are also the top 3 schools to go to for business school.

There are also no hidden gems down in the rankings - here are the only schools to send more than 5 grads not in the top-20 group. The lesson isn’t subtle.

UC-Berkeley - 11 grads (ranked #22)

University of Michigan - 11 grads (ranked #23)

Georgetown - 9 grads (ranked #24)

University of Virginia - 8 grads (ranked #26)

NYU - 6 grads (ranked #28)

Lesson #2: You don’t need an MBA – but if you get one, better be Harvard or Stanford

Graduate degrees aren’t highly valued in most of finance but an MBA is typically the sole exception. Venture follows that model to a T. 57% of the VCs didn’t have a graduate degree and of the 43% who did, nearly 85% were carrying an MBA. Firms differed in how much they valued MBAs (see below) but universally they weren’t buying stock in other programs.

Having an MBA is close to necessary at Lightspeed and Google Ventures, but not at Insight or Sequoia. The first three are easy to explain - Lightspeed and Google rarely hire people early in their career (<10% of their staff graduated from college in the last 5 years) whereas Insight is one of the three firms hiring a lot from that group - they, Bessemer, and Greycroft pull 25%+ of their staff from the recent grad pool. Sequoia uniquely both doesn’t hire recent grads and doesn’t hire MBAs. They just don’t value them at all.

Of the MBA programs, there’s a pretty clear hierarchy. If you can’t get into one of the top 5 programs, it won’t help. Harvard and Stanford together (informally, the top 2) make up more than half of the MBA cohort together. Nearly 1 in 4 venture capitalists overall have a degree from one of those 2 programs. That varies a bit by firm - it’s 55% of folks at Lightspeed - but it’s pretty clear that if you’re breaking into venture, that’s by far the easiest pathway.

These 3 elite MBA programs were also backdoor in for the third of venture capitalists who didn’t attend one of the top-20 universities. Of the 150 or so VCs in the dataset who didn’t go to a top undergrad, about a full third (47) went to one of these three business schools.

Lesson #3: There are multiple paths to the top

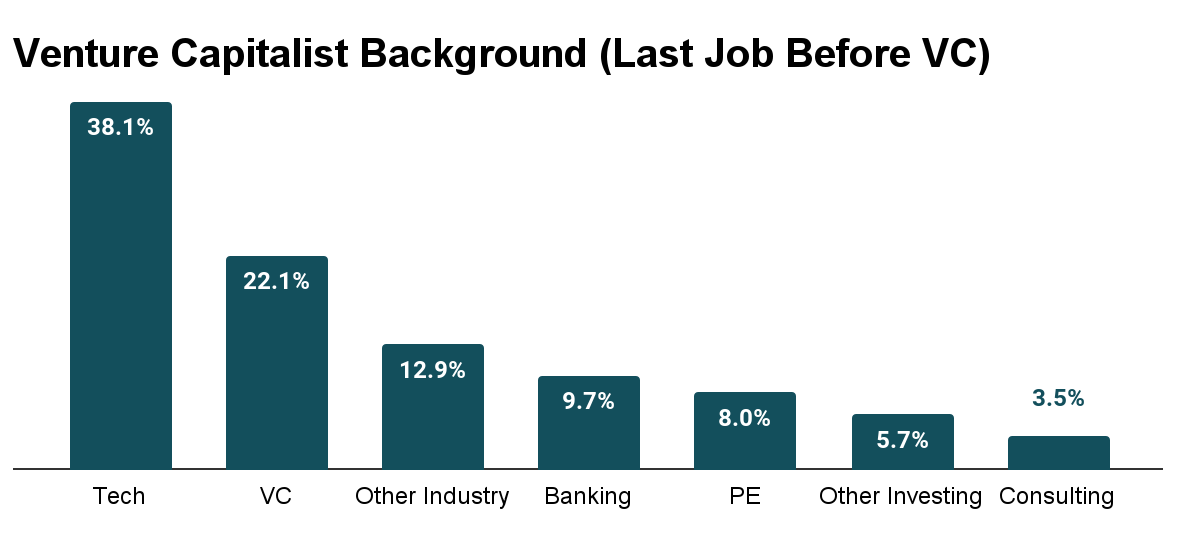

Looking at the career of these 450 venture capitalists, there were two main paths to VC. The split is about 50-50 between those who came from industry and those who came from finance (as defined by the last job they had prior to joining their current VC firm). Of those who came from finance, the vast majority had done VC investing at their past stop but a healthy proportion did private equity or banking. Insight is among the many firms which have expanded their recruitment from investment banking analyst classes, taking people just 1-2 years out of undergrad for their junior programs. Of those in industry, almost all were in tech - most from the same companies the VCs invest in.

The firms varied significantly in their background preferences, however. As you can see in the graph below, some exclusively prefer ex-banking and ex-VC types, while others (including, unsurprisingly, Google’s venture unit) tend to pull more from the industry ranks. Most seek to balance their investment committees with representatives of both sides.

Are there broader lessons to be taken from this? For those looking for a job in venture capital, surely. But otherwise - I’m not really sure. I’ve always believed that going to the most prestigious college you get admitted to (not the one you think is “best fit”) is probably the dominant career strategy if you want to make money and be in the highest-earning careers (finance, consulting, medicine, law). That jumps out clearly above. Does it matter that most of venture capital money is controlled by a cross-section of our nation’s top college graduates? Probably, but my guess is that’s true of most fields (maybe to be explored in a future post).

Please let me know what you think in the comments - and if you find this kind of stuff interesting, send it to a friend!